One student's experience - High School

By Zoe Dunn

I began Year 7 with trepidation and excitement, I was

thrilled to have the opportunity to learn more. However, I did experience

obstacles due to my disabilities. I am profoundly deaf, with bilateral cochlear

implants and have cerebral palsy. I used an electric wheelchair to navigate

school and utilised my FM in the classroom.

Throughout my high school years my teachers of the deaf

supported my learning. I had three itinerant teachers in the private system,

from years 7-10 and then one teacher in years 11 and 12, in the public system. Beginning

high school, I was glad to have the support of my teacher of the deaf who I had

in primary school. He supported me in my transition to high school and helped

me feel prepared. He also met with all my teachers and ensured they knew how

best to support me.

Despite this, there were instances where I did not receive

support, an example of this was my year 7 music exam. Even though my itinerant

teacher had informed the school of my needs, I was told to sit this exam with

no provisions. I do not hear music well and find it difficult to access. Nevertheless

I had to sit the exam, I was not given the required second listening, I was

forced to sit the exam without a scribe. My cerebral palsy prevents me from

being able to write, so this was near impossible. Needless to say, I failed.

In year 7-10, my itinerant teachers primarily helped me one

on one with classwork. I was keen to do well and found the workload

challenging, so I greatly appreciated the time I had with them to clarify

concepts that I may have missed in class. They were creative in their approach,

allowing me to do the work I wanted to do, while also including vital language

and comprehension into our discussions. Unfortunately, my itinerant teachers

were limited by the length of time they had with me, one hour per week, as well

as a school who did not understand my educational needs.

In Year 10, it became painfully obvious that this was not

the right school for me, especially for years 11 and 12. They provided the bare

minimum in terms of exam provisions, which were not appropriate for me and would

have ensured my failure in the HSC. In addition to this I felt like I was a

burden on the school and no longer a valued student but only an expense. This

attitude was not from my classroom teachers but from an unyielding

administration.

I moved to a local public school for years 11 and 12 and it

was the best decision I ever made. The new school welcomed me with enthusiasm

and warmth, such a contrast to my old school. They genuinely wanted to ensure

my success, I no longer had to fight to be heard. In consultation with my new

itinerant teacher, the school provided me with appropriate provisions to ensure

I was able to showcase my academic ability.

My new teacher of the deaf could provide me with six hours

of support per week, in contrast to the one hour I received before. With all

this time, she could provide more support which was especially important for

the last years of high school, through to the HSC. Not only did I receive help

one on one, I also had in class support, which I had not received since early

primary school. The HSC is a stressful time and she also helped me manage my

anxiety about exams and assignments. My itinerant teacher also encouraged me to

learn how to advocate for myself, a skill that has been really important in

school and beyond.

University was the next step and my itinerant teacher’s

support in my transition to tertiary education was invaluable. From helping me

choose courses, to attending meetings with disability services at various

universities, she really assisted me to make an informed decision about which

institution would be best for me.

I am forever grateful to the teachers I worked with, who

inspired me and encouraged me to see my deafness not as a barrier but to

celebrate who I am with it. I valued the relationships we developed and the

support they gave me, for without it, I would not be who I am today.

One student's experience - Primary School

By Zoe Dunn

I was an enthusiastic six year old when I started

kindergarten. I began school a year later than most of my peers to ensure that

my speech and language were well developed. While I enjoyed school and it was

where I started my lifelong love of learning, there were challenges pertaining

to my disabilities that made school life difficult. I am profoundly deaf and

have cerebral palsy. My physical disability affects my fine and gross motor

skills, so I have trouble walking and performing tasks such as writing. When I

began school I used a wheelchair and a walking frame, I also had a cochlear

implant, hearing aid and an FM.

Over the course of primary school I had four teachers of the

deaf and they supported my learning throughout. My itinerant teachers provided

assistance relevant to my needs at the time, they were dynamic and their

encouragement really helped me. I find it hard to remember exactly what I

needed in the early years so I asked my mum. She said that my itinerant

teachers provided the school with information about my deafness and strategies

to help access the curriculum. She also said that the regular contact from the

teachers about my progress was reassuring and she appreciated their support.

I remember struggling with learning how to read, which I

find ironic since I love to read now. In year 1, I recall I was only at Level 3

and felt ashamed because I knew I was not progressing at the same rate as my

peers. My itinerant teacher really helped me by working one on one with me in a

supportive environment. Due to my cerebral palsy I found tracking words along a

page difficult, in conjunction with traditional obstacles. It took dedication, patience

and at times a reminder of where I was on a page but I did learn how to read.

This was an accomplishment and it opened a whole new world for me to explore

and provided me the opportunity to learn more through books.

I also worked on my comprehension with my teacher of the

deaf in Year 4 and would look forward to our weekly sessions. I enjoyed reading

the passages and was encouraged to think more deeply about texts. Comprehension

is now a strength of mine and I consider the work I did with my teacher pivotal

to my understanding. It has really helped me with my schooling, through to university.

I am not intimidated when I read research papers even though it seems a foreign

language with all that jargon!

When I was 10 years old I received my second cochlear

implant. I found this time very challenging as I was uncertain and doubted the

need for the second implant as I felt that I heard well enough with my first.

My itinerant teacher worked alongside my speech pathologist, who was doing the

auditory verbal therapy. It was extremely difficult to learn how to hear

through the new device, everything sounded strange, so naturally, I did not

want to wear it to school. My itinerant teacher encouraged me to wear it and

helped me accept my new auditory environment. She worked to alleviate my

anxieties and motivated me to think positively about the experience.

My teacher of the deaf was important with my transition to

high school. I had the same itinerant teacher from year 6 to year 7 and this

gave me some continuity when everything else was changing. He helped me with

the shifting expectations and logistics that are unique in high school. Also, he

met with all my teachers and helped them understand my needs in the classroom

as a deaf student.

I feel privileged to have worked with so many amazing

teachers, who inspired me and encouraged me to recognise that my disabilities

are not a barrier to success. I really valued the relationships I developed

with my teachers in those early years and remember them fondly.

The Hearing Check that’s Child’s Play

By Carolyn Mee

“Children need to hear to learn but all too often undetected

hearing problems cause children to fall behind during Primary School until

someone thinks to have the child’s hearing checked. By the time this happens

the child may not only be behind academically but may have come to deeply

believe that he or she will never be able to keep up with the other children at

school.” Professor Harvey Dillon,

Department of Linguistics Macquarie University. 1.

In Australia, all babies

have access to a hearing test at birth. The newborn hearing screening program

is aimed at identifying children with moderate or greater hearing loss to

ensure they receive timely intervention, such as cochlear implants or hearing

aids, so they can hear in order to develop language and auditory brain

function. 2

In addition to mild loss, which

may not be detected by the newborn screen, there are other forms of hearing

issues that can develop in the years after birth. Illness, injury and genetics

can cause a child to develop debilitating hearing issues that if left untreated

can have a profound impact on their life.

It may be a surprise to learn

that more children are fitted with hearing aids during the first three years of

school than are fitted in the first year of life. 3 This may be due to their loss being mild

and hearing aids being unnecessary prior to school or it may be due to their

loss going unnoticed until learning issues at school trigger investigation.

If the child’s hearing loss

is due to a middle ear issue such as glue ear or wax, medical intervention may resolve

the issue. It’s estimated that more than 10% of children suffer from middle ear

issues and the impact of a middle ear issue can, if left untreated, be as

significant as that of a permanent hearing loss.

In addition to middle ear and inner ear hearing issues there

are a large number of children who have hearing disorders not in their ears,

but in their brains. Dr Harvey Dillon states that ‘some of these brain-based

issues are the consequence of middle ear infections the children had when they

were infants, toddlers or preschoolers’.

For those children who

don’t have their hearing loss identified early - which can depend on informed

and observant parents and teachers - it can take years to catch up both

academically and emotionally. It’s for this reason that access to a hearing screening

solution, particularly at school entry, is so important and why Sound Scouts

was created. Working with Professor Harvey Dillon, the Sound Scouts’ team recognised

the opportunity to combine the engagement delivered by play, with the science

of a hearing test, and the accessibility made possible by digital technology,

to create a hearing screen that every schoolchild in Australia could take,

every year if desired.

In its development, Sound

Scouts was trialed with over 1,000 children, aged from four years, through to

teenagers across a range of preschools, schools and hearing organisations. The

trials involved all children being tested by both a paediatric audiologist and

Sound Scouts. The game achieved a high level of specificity (98%) and

sensitivity (85%) for those children receiving a pass or fail result. 4

Sound Scouts is designed to

be played in a quiet, distraction-free space with adult supervision and good

quality headphones. Those being tested complete three game-based listening

activities. Two are based on perceiving speech, one

in noise, one in quiet, and the other is listening to tones against a noise

background. Each of these tests constantly adapts so the child/player is always

listening at the edge of their hearing capability.If the child has a hearing problem they aren’t made aware

of this while playing. It’s also important to note that the results are age

adjusted to account for improved speech perception and concentration.

The app screens for conductive

and sensorineural hearing loss. Sound Scouts has also been designed to test for

listening difficulties in noise (including spatial processing disorder which is

a brain-based hearing issue) which results in unclear perception of speech when

background noise is present. If a child is found to have listening difficulties

in noise further investigation by an audiologist or speech pathologist is recommended.

At the very least the teacher should be made aware that the child has

difficulty hearing in noise and should be seated at the front of the class.

Sound Scouts is a

screening solution and has been created to provide an indication of childhood

hearing issues (4yrs+). The newborn hearing screen is wonderful but it is not a

lifetime guarantee of good hearing which seems to be the misconception that

many parents are now under. As a company, Sound Scouts aims to raise awareness

about the importance of hearing and the potential for hearing to change at any

time. Technology, when carefully tailored to the task, which we believe Sound

Scouts is, can make the impossible possible, in this case providing a solution that

will allow all children to have their hearing tested at school entry and

anytime thereafter.

1. Sound Scouts video, 2014

2. Neonatal Framework for Neonatal Hearing Screening August 2013

3. Hearing Australia Background Paper for Senate Select Committee on Health

4. Harvey Dillon, Carolyn Mee, Jesus Cuauhtemoc Moreno & John Seymour

Hearing tests are just child’s play: the sound scouts game for children entering school, Pages 529-537, International Journal of Audiology,

Consonant Acquisition in Different Languages

McLeod, S.,

& Crowe, K. (2018). Children’s consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A

cross-linguistic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(4),

1546–1571. doi:10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0100

As teachers of the

deaf, a sound understanding the typical development of consonants in children’s

speech is a requirement. Normative data on the acquisition of consonants in

English, including Australian English, is readily available. We know that for English most children will develop consonants such as

/p/ and /m/ earliest and /θ/ latest. We know that by the time children are 5-years-old the

majority of children will be able to use the majority of English consonants

correctly and will, on average, have percentage consonant correct scores of

over 90%.

However, what happens

when the child you work with speaks a language other than English? What do you

know about typical patterns of consonant acquisition in languages other than

English?

McLeod and Crowe (2018) recently published a review of studies

examining consonant acquisition in the American Journal

of Speech-Language Pathology. Included in the review were 60 papers describing 64 studies of

consonant acquisition in 27 different languages: Afrikaans, Arabic, Cantonese, Danish, Dutch,

English, French, German, Greek, Haitian Creole, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic,

Italian, Jamaican Creole, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Maltese, Mandarin,

Portuguese, Setswana, Slovenian, Spanish, Swahili, Turkish, and Xhosa. Dubbed

“That one time a journal article on speech sounds broke the SLP internet” (The Informed SLP), this systematic review has caused intense

discussion among the speech-language pathology and educator community as

representing ‘new’ norms for age of consonant acquisition in typically

developing children.

In this

paper there are four main sections:

- Data

from the 64 studies were analyzed and presented in the paper in terms of the

consonants that children acquired to the 75-85% criteria and to the 90-100%

criteria and the mean age of standard deviation for the acquisition of each

consonant is given. - The

accuracy of consonant and vowel production is also examined across languages

with mean values for percentage consonants correct (PCC) and percentage vowels

correct (PVC) presented for children of different ages. - Patterns

of acquisition based on the features of consonants such as manner and place of

articulation are also discussed. - For

languages where there were multiple studies that described consonant

acquisition, case studies are given and consonants are grouped by their use at

the two criterion levels (75-85%, 90-100%) at 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 years of age.

The languages described are English, Japanese, Korean, and Spanish.

How can this article

help you in your work?

- Whatever

languages the children you work with speak, understanding the ages at which

particular consonants typically develop, particularly consonants that are not

part of the English phonemic repertoire, can be helpful in monitoring

development and guiding intervention. Examining the mean,

standard deviation, and range of ages at which a consonant is acquired across

languages can be a helpful guide. - Understanding

the patterns that govern which consonants are typically acquired earlier and

later across languages gives a sounder foundation to base intervention goals of

for children who use languages other than English. - Even if

all the children on your caseload speak English, and only English, there is

still something for you as this article updates the norms for English consonant

acquisition based on more recent publications than are typically used.

Other resources that

can support your understanding of consonant acquisition across languages are

available on the Multilingual Children’s Speech website.

- Inventories:

Information on the consonant inventories of a large number of languages is

available here http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/languages - Assessments:

A list of speech production assessments in a range of languages is available

here http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/speech-assessments - Research: A

list of studies that describe consonant acquisition by language across many

languages and dialects is available here http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/speech-acq-studies - Video: A

video presentation about this paper is available here https://speakingmylanguages.blogspot.com/2018/11/childrens-consonant-acquisition.html?m=1 - Free graphics

about consonant acquisition: English consonant acquisition: Treehouse (A4 .pdf), Steps (A4 .pdf), 4 languages: English, Japanese, Korean and

Spanish acquisition (A4 .pdf)

By Dr Kathryn Crowe

and Professor Sharynne McLeod

Morphology: The Missing Piece of the Literacy Pie

Since

the early 2000’s, researchers have focused on five subskills deemed critical

for readers to obtain while learning to read English: vocabulary, phonology,

decoding skills, reading comprehension, and fluency. While there is little argument that these five

skills are critical, a subskill seems to be missing, morphological

knowledge. Considering that English is a

morphophonemic language (print English represents meaningful word parts as well

as a phonological code), it seems logical that phonological and morphological

instruction would be important to decoding the language while reading.

Morphological

knowledge includes understanding that morphemes are the smallest part of

language that still has meaning, being able to break words apart into their

morphemes (e.g., happiness can be broken up into happy and -ness),

and being able to follow rules to combine morphemes to make new words (joy

and -ful are combined to make joyful). Morphemes fall into two categories:

inflectional and derivational.

Inflectional morphemes change the tense, number or gender of a word and

provide readers with clues about the grammar of a sentence. Take the sentence “The boy is walking.”, the

inflectional morpheme -ing tells the reader that the act of walking is

ongoing. Also the lack of an -s on the

word boy tells the reader that there is only one boy walking. The second type of morphemes are derivational

morphemes. Derivational morphemes are

combined to make new words or are used to change the class of the word. When you add -ful to help, the noun

or verb help becomes the new word and adjective helpful.

Teaching

morphemes meanings and how to break apart or combine words is helpful because

the English language is more regular in the way it is written than in the way

it sounds. For example, the words heal

and health have the same morpheme heal.

Although they are spelled the same, the words sound different. Readers can use the spelling pattern to help

them figure out the meaning of an unfamiliar word. Also, teaching morphology gives the students

a way to generate vocabulary knowledge on their own. About sixty percent of new words can be

decoded using morphological knowledge. If

you teach students that bio- means life, they are able to get the gist

of words like biology, biography, and bioluminescence. On the other hand, if you only teach students

how to sound out bio- using their phonological skills, they may have no way to

understand what the word means. Students

who receive morphological instruction have the ability to decode for meaning

when reading.

In

addition, morphological knowledge continues to develop and support reading

comprehension after phonological skills have plateaued around the age of eight

or nine. Morphological knowledge also

makes a unique contribution towards reading comprehension because it supports

word knowledge in a way that phonology cannot.

For the reasons listed, researchers are encouraging educators to add

morphological instruction to their daily reading lessons. Morphological instruction benefits readers

with and without disabilities as well as deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH)

readers.

DHH

students’ struggle with reading has long been documented. Some believe that DHH readers get stuck at

the very basic level of reading, decoding.

There are at least two reasons for this: vocabulary knowledge that is

not equal to that of their peers who are hearing and delayed morphological

knowledge that starts in preschool and persists to college. DHH

readers experience delayed English morphological knowledge because they may not

hear the morphemes in spoken language and the morphemes are represented

differently in signed languages. Both of

these situations lead DHH students to being underexposed to morphemes causing a

delay. To ameliorate the delay, teachers

of the DHH (TODHHs) can provide morphological instruction through spoken or

printed English.

When

teaching morphology, TODHHs should include the following instruction: (a) how

to recognize component morphemes within words that have multiple morphemes, (b)

the morphemes’ and root words’ meanings, and (c) the rules to create new words

from morphemes. For example, a text may

contain the word immunology. Immunology can be broken down into immune and –ology. Immune is the root

word meaning resistant to a particular

infection and –ology is the

suffix meaning the study of. First,

the student learns to recognize these two parts of the word. Second, the

student learns to define the word parts. Third, the student learns how to put

the meanings together to define the full word (i.e., Immunology means the study

of resistance to infection). Fourth, the student attempts to decode the word

with meaning in context. Last, the

student and TODHH look for other words that also include that morpheme and

practice determining the meanings of those words. Often, one morpheme can be found in 10 or

more new words. For more information,

check out this link: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/readingviewing/Pages/litfocuswordmorph.aspx

Jessica W. Trussell, Ph.D.

National Technical Institute for the Deaf

Rochester Institute of Technology

Rochester, NY, USA

Further reading

Trussell, J.

W., & Easterbrooks, S. R. (2015). Effects of morphographic instruction on

the morphographic analysis skills of deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Journal

of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 20(3), 229–241.

https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/env019

Trussell, J.

W., & Easterbrooks, S. R. (2017). Morphological knowledge and students who

are deaf and hard-of-hearing: A review of the literature. Communication

Disorders Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740116644889

Trussell, J.

W., Nordhaus, J., Brusehaber, A., & Amari, B. (2018). Morphology

instruction in the science classroom for students who are deaf: A multiple

probe across content analysis. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education,

11(3), 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.60.8.4

Interactive Storybook Reading: A Vocabulary Instructional Strategy

Interactive Storybook Reading: A Vocabulary Instructional Strategy

Storybook reading is one of the most effective ways to improve the language and reading outcomes of children (Swanson et al., 2011). This remains true for students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing (DHH). Storybook reading influences language and reading outcomes through vocabulary. There are different types of storybook reading: shared reading, repeated reading, and interactive storybook reading. Shared reading is reading aloud a story to children with a focus on comprehending the story and story elements, such as character, setting, and plot. Repeated reading is reading the same book with children over and over again to build confidence and repeated exposure to the story. Interactive storybook reading is using the book as a shared experience and developing language in the context of the story. Interactive storybook reading has shown to be effect with children who are DHH who use sign language (Trussell, Dunagan, Kane, & Cascioli, 2017; Trussell & Easterbrooks, 2014) and spoken language (Trussell et al., 2017; Trussell, Hasko, Kane, Brusehaber, & Amari, 2018) from the age of three to about six years old.

Interactive storybook reading is easy to plan for a class or one child. There are different goals for interactive storybook reading. The first goal is to develop vocabulary. The second goal is to help the child retell the story. Herein, we will focus on the first goal to develop vocabulary. When using interactive storybook reading to develop vocabulary, the focus of the instruction will be on the book’s pictures and not the text.

First, you should pick a book that has little text but very clear pictures with a lot of action. Second, you will need to look at the book’s pictures and notice items that show up in several pictures throughout the book. These are the items that could become your target vocabulary. After making a list of potential vocabulary items, you may want to pretest your students to determine if they know the words or not. You can use the picture from the book or you could develop flashcards using colorful clipart. Next, you can choose as few as five vocabulary items to focus on and as many as ten depending on your students’ needs. Now that you have the vocabulary items that you will focus on, it is time to develop your questions.

Interactive storybook reading is centered around two concepts: CROWD question prompts and the PEER cycle. The CROWD question prompts are five different types of questions that are asked during interactive storybook reading. The first type is the completion question (Dad is holding an _________.) The second type of question is a recall question from the pictures (How were the children feeling before?). The third type of question is an open-ended question with more than one right answer (What do you think the children see?). The fourth type of question is a wh- question (What is on the ground?). The last question type is distancing and connects the story to the child’s life (When have you felt the same as the dad feels here?). The purpose of the questions is to elicit the target vocabulary items from the child. You will write four to five questions for each vocabulary item throughout the book. Attempt to write various types of CROWD questions to elicit the vocabulary item.

The next important part of interactive storybook reading is the PEER cycle. The first part of the cycle is prompting using one of the CROWD questions you have developed. The second and third parts are to evaluate what the student said and expand on it. The last step is to re-prompt the student with the CROWD question again in hopes that the student will give you a longer response. See the example below for further clarification.

PEER Sequence Example

| Adult | Child | |

| Prompt | What fruit do you see here? | Apple |

| Evaluate | Yes! | |

| Expand | You see a red apple. | |

| Re-prompt | What fruit do you see? | Red apple |

Initially, you will be giving the student the answers to the CROWD questions prompts. After the second exposure to the book, the students should start answering with the vocabulary target you were hoping they would use. You can use the book for four to five days or until the students have mastered all of the targeted vocabulary items. The students enjoy repeating the book day after day because they feel very successful when they can answer your questions. When engaging in interactive storybook reading using the PEER cycle, the teacher and students can have 50-60 opportunities for engagement with the CROWD question prompts. If you would like to read more about interactive storybook reading, also known a dialogic reading, see these links for examples and more information: http://www.getreadytoread.org/early-learning-childhood-basics/early-literacy/dialogic-reading-video-series.

Swanson, E., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., Petscher, Y., Heckert, J., Cavanaugh, C., … Tackett, K. (2011). A synthesis of read-aloud interventions on early reading outcomes among preschool through third graders at risk for reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 44(3), 258–75. http://doi.org/10.1177/0022219410378444

Trussell, J. W., Dunagan, J., Kane, J., & Cascioli, T. (2017). The effects of interactive storybook reading with preschoolers who are deaf and hard-of-hearing. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 37(3), 147–163. http://doi.org/10.1177/0271121417720015

Trussell, J. W., & Easterbrooks, S. R. (2014). The effect of enhanced storybook interaction on signing deaf children’s vocabulary. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 19(3), 319–332. http://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ent055

Jessica W. Trussell, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

National Technical Institute for the Deaf

Rochester Institute of Technology

jwtnmp@rit.edu

The evidence base for our primary role

The evidence base for our primary role

It is almost out! 664 pages detailing Evidence-Based Practices in Deaf Education will be published this October, for £64. It is edited by the prolific sponsor and coordinator of research in this area, Marc Marschark, with Harry Knoors with a world-wide list of contributors. A quick scan of the contents indicates that it addresses issues that we deal with constantly: The diversity of our students, supporting language, assisting with literacy and numeracy, and enhancing cognitive and social-emotional development.

So what would we like from such a book? We might dream that somewhere out there is an instruction manual for that student that we can’t get out of our minds as we drive from one school to another, or to work. Perhaps there exists a set of lesson plans, with attached resources, finely attuned to that student, who like many others, has the paradox of great potential, but huge gaps in his skill set? Returning to reality, however, I would like to point briefly to three articles from our Deafness and Education International Journal (DEIJ) that can serve to remind us of basic daily realities. The articles concern Language and Play, Numeracy, and Executive Function.

Our own Margaret Brown from Victoria and Linda Watson from Birmingham have stepped down from many years of voluntary editing the DEIJ with a wonderful collaborative article synthesizing studies in the early language and literacy development of deaf children (Vol. 19 pp.108-114). A wonderful must-read for any of us working with prior-to-school aged children and their families. It reviews the significant literature and concludes that practitioners need to focus not on their interventions with the child, but with assisting the parents to utilize the everyday and ‘exotic’ experiences they have with their child. Pretend play should be a strong focus, and a means of providing quality scaffolded-interactions. We know most of this, but in the era of reductionist SMART goals, we may need reminding that play-based and parent-focused strategies are necessary to effectively assist language development, even with students at school with delayed language.

Two articles in Volume 20:2, both with Marc Marschark as a collaborative editor, give a sense of what is to come in the impending book. The first deals with numeracy and includes a discussion of real-world estimation abilities (number, length, weight, volume) – abilities that are also related to everyday living skills as well as to academic performance. Apart from yet again establishing that the deaf learners are behind their hearing peers–even though this gap is unrelated to cognitive abilities–there were few indications of what we can do about it apart from avoiding generalizations for the actual students we are supporting. There were also strong suggestions that language ability is a mediating factor, including the way in which it can limit everyday interactions and negotiations with pre-school children. There was also yet another warning that the early benefits of early intervention and cochlear implants seems to diminish over time, i.e. starting school well does not mean that they will not need continuing assistance over their school life.

The second article in Vol.20:2 relates to social maturity, executive function and self-efficacy. Even though the research was with deaf university students, it provides access to current thinking in all these areas with our students. New for me was the Learning, Executive, and Attention Functioning (LEAF) scale as a research measure, which includes comprehension and conceptual learning, factual memory, attention, processing speed, visual-spatial organization, working memory etc. There is a lot of other interesting detail in this study, but I was struck by one of the conclusions: Social maturity was a key issue for both executive function and self-efficacy, and that this was strongly related to spoken language between hearing parents and their deaf children. This once again indicates to me that a family centred approach that strives to enhance communication at home may be the best focus of our activities and energy. Rather than lie awake thinking about how we will engage with a particularly difficult student, we may be better engaged thinking about how to assist the parents to engage more with their child – reading to them, arguing, sports, games together, homework time etc.

So, I am left wondering about our primary role: obviously as a parent coach in early intervention, and perhaps still as a parent coach all through school? Or is our role to work to find other ways to increase the amount and quality of the interactions that our students have, with anyone, independent of us?

By Dr John Davison-Mowle

The Importance of the Ling Sound Check

Many of us perform the Ling test everyday but what do the results actually mean? We thought it might be helpful to provide some more detail to help you implement this listening check in your daily practice.

Listening Check

Remember that this is just a listening check. The Ling test checks the hearing access of the person being tested throughout the full speech spectrum. We are looking for a clear detection response- a repeatable, consistent response to the sound. With little children it might be a nod, a smile or a change of breathing. With toddlers, we might ask them to put a ring on a stacking pole or put a marble in a jar because their physical development allows them to control this motion after that age of 18 months. Ideally, move to an identification response as quickly as possible- this is a repetition of the sound. This is where problems can occur. Not all the speech sounds are developed at the same time. Children take longer to produce /s/ and /sh/ accurately than they do with the other sounds. Don’t fall into the trap of trying to remediate the speech sounds. The Ling test is a listening check only! If the child cannot produce the sounds correctly, perhaps use the Ling cards or toys that match the objects and have the child point to them at the same time that they are saying the sounds so you can be sure they are identifying them correctly. If the child can indicate that they heard and identified the sound correctly then you know they have good auditory access.

Multiple devices

We are so lucky in Australia to have such great access to hearing devices for our families. The vast majority of our clients are fitted bilaterally with the best hearing technology in the world. This means we need to check that both the devices are working! Test each ear separately so that you can ensure that they are working correctly, and then test them together to see if there is an additional binaural hearing effect. If the child wears an FM, test with that. You don’t need to do all 4 tests every day but get into the habit of checking the individual devices whenever there is a concern about a child’s hearing.

What if there is an error?

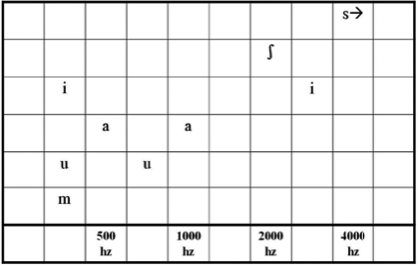

It is also important to know what an error might mean. Lets go to an audiogram to look more closely at each sound:

The sounds are recorded on this audiogram using the phonetic alphabet. You will note that the vowel sounds have 2 formants or vibrations recorded while the consonant sounds have just the first formant listed. This helps us to recognise where the problems are when a child makes an error.

/m/

This is the lowest frequency check and measures responses at this low pitch. If a child confuses or doesn’t respond to /m/, then they may struggle to hear other sounds of low frequency. We use our low frequency access to develop speech with normal tune or prosody- the musical quality of our voices comes from our ability to hear these low frequency sounds.

/u/ (sounds like /oo/)

You will note on our audiogram that /u/ has each of its formants in the low frequency range. Sometimes children confuse /u/ and /m/ which may indicate problems with low frequency access. There are many vowels that sit in the low frequency range and a clear response to /u/ tells us the child will be able to access these as well.

/ah/

The formants, or vibrations for /ah/ occur in the centre of the vowel range. If children have poor access to /ah/, they may also have trouble hearing unstressed words like articles (a, the) and unstressed sounds (-ed, -es). This can lead to the child speaking and writing with grammatical errors.

/i/ (sounds like /ee/)

This is the most important sound of all! Take a look at the audiogram- one of the formants sits in the low frequency bands and the second sits in the high frequency bands. If the child doesn’t respond at all, there is a problem with their overall access! If they say /u/ when you ask for an /i/ repetition it indicates that they have problems with their high frequency access. If they say /s/ when you ask for /i/ repetition then there is a problem with their low frequency access.

/sh/

Children with conductive and mild to moderate high frequency losses often have less experience hearing the high frequency sounds like /sh/. It may take them longer to learn to attend to this sound if they are amplified later.

/s/

As with /sh/, this sound may be unfamiliar to children with conductive and mild to moderate high frequency losses. It may take them longer to attend to this sound. Access to high frequency speech sounds allows us to discriminate, identify and comprehend running speech. It allows us to recognise sarcasm and irony. It helps us to hear plurals and possessives. It ensures that we can tell the difference between each word in a sentence, attend to each word and draw meaning from it. It is integral to good communication to be able to access this sound.

Performance Details

Begin doing the test close to the child in a quiet environment- no further than 1 metre away. Take away all visual cues so the child is just listening and not lip reading. If you choose to cover your mouth, ensure it doesn’t interrupt the flow of air and muffle the sound.

If the child can perform this successfully, first add distance- 2 meters and then all the way to 5 metres. This gives you a range of the child’s best listening in good environments- helpful to share with teachers. Once they are consistently responding at distance, add noise. Often that is already in place in noisy classrooms but if not, add sound from a radio or your phone. Classrooms are rarely quiet environments and its useful for the child to learn to discriminate speech sounds over the top of background noise.

Hopefully this has been helpful! What strategies and activities do you use when you perform the Ling check? How do you manage this in a busy classroom? Do you coach your mainstream teaching colleagues about how to do this? We’d love to hear your thoughts!

Author: Trudy Smith, IST:H and EDSA President